Repetition is not repetition…

‘Repetition is not repetition’ Pina Bausch. Discuss.

Florence barshall

‘Repetition is not repetition’, Pina Bausch.

Introduction

Analysing creative practices, I will reimagine how ‘Repetition is not repetition’, Pina Bausch. I will be arguing that in nature and creativity, this is the case because repetition is generative. In nature and creative processes, repetition generates an emergent property.Repetition is always in a state of becoming with and is never a perfect repetition of what came before. However, these emergent properties and imperfections are often stifled in industrial and machine repetition, which I will also explore in contrast to more organic repetitions in art and the natural world. The stories I will be referencing are Martin Shaw’s telling of Wolverine Makes the World and also The Bone Woman. I will be illustrating these ideas by making the structure of my essay a montage of thought. I will write in this form to explore how the weaving of thought itself can be considered a form of intelligence that is lateral and interconnected.

Patterns of thought and ideas are presented in new forms, in new relationships and constellations, as Homer described the role of the poet as a stitcher of tales (Pantelia, 1993, P.7). Throughout the essay, I will see how the act of creative repetition generates the following properties, among others: imperfection and evolution, Emotional resonance, forms of knowledge, Spontaneity, Healing, Transcendence, Flow states, Architecture of thinking and finally, unity and Connection. These properties counteract the alienation that occurs when we try to ‘copy and paste’ the world perfectly. I will be citing examples of this in the arts, from ancient oral storytelling and ritual activity to contemporary forms of creation. In these ways, I will be exploring how repetition is not repetition – a paradox that accounts for less linear aspects of life and more woven forms of intelligence, that are perhaps closer to oral ways of seeing. I’m going to outline why repetition is never really repetitive because it is in constant evolution and relation. I’m going to explain why from my perspective, we need to honour this natural and imperfect repetition, particularly in the times we find ourselves in.

Industrial VS Creative Repetition

In the natural world, this holds true, ‘repetition is not repetition’. However, this is not the case in the industrialised landscape where attempts at perfect replicas can be made. This can lead to a lot of negative effects. Some technologies facilitate poetry and natural creativity while others inhibit it, to different degrees. Martin Shaw distinguishes between trapping and trailing stories. Attempts at perfect repetition are antithetical to the diversity of nature itself, which is repetitive yet also manifold. Landscapes of monoculture – of thinking, being, and learning are essentially unsustainable. A ‘pattern of one-dimensional thought and behaviour’ is created itself through industrial repetition (Marcuse, 1964, P.96). It correlates with destruction, disease, and ill health because an attempt to perfectly replicate and reproduce without emergent properties, is unsustainable. When we try to suppress the emergent properties of repetition (ie. The imperfection of an apple), we are fighting against nature and creativity, like Capitalism. Modern man thus becomes ‘alienated... transformed into a commodity’ (Fromm, E., 1957, p.131). This goes against organic reciprocal relationships, in which creativity enables, imperfect, organic repetition. For example, some repetitive formulas, such as the Fordism movement, suppress human creativity to put us on a production line. This attempt at perfect repetition is simply suppressive and stifling to human nature. It also ignores the limitations and beautiful forms of imperfect change. The idea of ‘natural capital’ which can grow and be repeated indefinitely ignores the essence of our biosphere and its limitations (Schumacher, 1973, P.23). Currently, many things have been industrialised: from education to the food system, to the entertainment industry. Like attempts to perfectly reproduce a carrot again and again: it results in disease. The same can be said for thought, entertainment, and educational processes. As I have outlined, the innate imperfection of repetition is at the core of nature and sheds light on the creativity and uniqueness of all natural things. To deny this is to attempt a movement against nature. I will continue my inquiry into the emergent properties of creative repetition.

Oral culture and other forms of art honours the nature of repetition and its emergent proportions, unlike industrious systems, and I will now elaborate on this. I will be seeing how the following repetitive forms open a space for natural emergent properties: Dance, Story, Nature, and Ritual. The repetition is changed by these actions in regard to specific natural being, specific feeling, specific connection and resonance. Thus, spaces that facilitate and celebrate imperfect repetition, such as creativity, can be seen as a necessary form of research and inquiry into new ways of being, seeing and thinking, that are fresh; that place us in a creative dialogue with the world and nature. This is the diversity that makes life beautiful: ‘It is part of the battle against sameness. Differences - eternal differences, planted by God in a single family, so that there may always be colour’ (Forster, 1989). I have just distinguished between different forms of repetition and the consequences of valuing one over the other. I will now track repetitions more specifically in nature, culture, and story.

Repetition and relationship

In the context of oral storytelling, ‘repetition is not repetition’ as each telling is relational and therefore diverse. The medium of story was seen in the oral culture as a vital form of intelligence in itself which could be repeated but was never quite the same. The act of repeating without complete repetition led to the evolution of the story. ‘The Hebrew term ‘Dabar means ‘word’ and ‘event’’ at once, implying that in oral culture, words were spoken and related to a particular relation and moment (Ong, 2011, P.43). Although a pattern is repeated, it’s never exact, as the teller animates the story with their own uniqueness. This is important because if all knowledge was perfectly repeated, then there would be no free thought and dialogue. Many scientific discoveries were made through imperfect repetition of instruction. For example, a talk between Brian Eno and James Bridle analyses relational intelligence and how many forms of knowing are dependent on in the moment ‘relational’ understanding, which can be repeated but always imperfect and changed, depending on the set of relations it is in the context with (Eno, 2023). In the story of the Muskrat, nature is created via repetition, imperfect repetition, which opens a continual process and unfolding of creativity. In oral culture, the same material is or is presented as fresh in new relation: to land, persons or woven differently, as it is repeated over generations. For example, in Ways of Seeing, Berger explores how the artwork is dependent on the ‘uniqueness of the place where it resided’, especially before the industrialisation of art (Berger, 1972, P.25). In the natural world, in the act of repetition, each repetition goes beyond itself, becoming imbued with extraneous significance. Because we live in an immutable, imperfect world, no form can be perfectly repeated. For the Oral storytelling tradition, this makes significant the specific telling as ‘Storytelling is inescapably visceral... in relation to others’ (Scott, 2018, P.44). In Martin Shaw’s telling of Wolverine Makes the World, desire itself takes on a repetitive quality. The desire at the start of the book is a repeated emotion - a longing that is rhythmic and continuos. Through a repetitive emotion, diversity emerges. Desire is initiated by relationship - a relentless feeling for the ‘one who wiggles nicely’ and sets Wolverine in motion, along with his companions - the badger, beaver and Muskrat. The repetition of swimming through the water, deeper and deeper, almost like going back to the source of the river Lethe, which we do again and again, is itself an evocation for infinite difference (Schwartz, 1991). In other words, the repetitive actions provoked by desire are not exactly repetitive, for the emergent properties are vast and striking. Swimming to the source of water, much is unveiled and the continual blowing on the ass of the muskrat produces creativity itself and true diversity. This shows that oral culture honours relational intelligence, which is diverse in each moment and repeated pattern. I have just assessed relationship to place and person, as the particularity that makes oral culture a space for imperfect repetition.

Repetition and Emotion

‘Repetition is not repetition’ because it is emotionally evocative and particular. I will explore the idea of emotion as an emergent property of repetition, making each repetition imperfect. Resonance is the strength of a ‘relationship’ to the world which opposes ‘cold ‘pure’ economic rationality’: the difference being ‘interactions… (or) being moved’ (Rosa, 2019, p.5). The specific experience of intense emotional connection, between subject and object, makes each repetition diverse in an art form. Resonance is seen in the text about the Bone Woman. The monotony of the town is broken up. In the steady, repetitive stream of men and suitors, the emergent difference and resonance is when the bear brothers come to the door. This signifies a change in the narrative, a breaking away from old patterns due to an emotional resonance which then creates action. We can see that the resonance of attraction between the woman changes the tone of the story and patterns are broken up, carving new path ways. Later in the story, Repetition is seen to have the emergent property of healing or re-membering the body. The idea of ‘weav[ing] yourself back to oneness (via) ritual’ (Macleod, 2023, P.4) is fascinating. In Martin’s telling of the story of the Bone Woman, the lady is re-membered through the drumming and ceremony, which reincarnates her flesh, which had been eaten away. The dance is evocative and repetitive, almost like the healing of the body and self-seen in Vinyasa flow yoga: the repetitive flowing action allows for the body to heal. Similarly, Art therapy often provides containers for imperfect repetitive activity such as dance or ritual to allow for healing and connection to occur as a ‘type of psychopesis or soul-making’ (Wood, 2022, P.22) which contrasts fragmenting repetitive activities that are industrious and alienating. In other art forms, the beauty of the dance, for example, is found in its resonance, which is a state that cannot be replicated and can only be sensed in real-time. The dancer embodies a slightly different emotion each time, even if dancing the same motions physically, which links to the Pina Bausch concept directly. The imperfect repetition of anything, whether it be a dance, ritual, song, story, script, pattern in nature, or form of art, produces an emergent quality which allows us to emotionally connect to it. Emotion animates something and Pina Bausch refers to a kind of transcendence – ‘who can tell the dance from the dance’. Emotions are as Diverse as anything, like nature, which means repetition is affected by how each form is animated. Nothing can be repeated perfectly because emotional experience is particular and thus repetition is not repetition. I have illustrated how the diversity of emotion means each repetition has a different emergent property. I will now explore improvisation as another emergent property.

Repetition and improvisation

‘Repetition is not repetition’ because it provides the form for improvisation and spontaneity. Through repetition in a creative practice, a space grows for improvisation to occur. In fact, in the arts, structure itself could be said to support improvisation (Peters, 2012, p.15). For example, in oral culture the different resonance of each performance changes each recounting: in repetition, a space grows for randomness. In the text of the Wolverine, there is space for improvisation within a set form: because the story is retold again and again, improvisation can occur when the teller evokes different artists whom they resonate with and differing cultural icons depending on their own context and individual attraction. For example, while Martin referenced Leonard Cohen as a cultural icon, in my creative retelling of the story, I mentioned Frida Khalo. Thus, there is creative and improvisational liberty provided by the structure of the story. In other art forms and oral cultures, such as Flamenco culture, songs are passed down generations and repeated but each has an emergent property of spontaneity for the particular artist. The same can apply to jazz: the repetition of jazz opens a space for a spontaneous and sometimes ecstatic flow. This links back to the story, where the blowing upon the ass of Muskrat is a highly repetitive action but itself invokes infinite differences, like jazz improv. As Martin tells the story, the rhythm of the drum holds a space for the story to be told with a degree of natural improvisation, never perfectly repeated. The repetition facilitates the journey of the story. In this sense, repetition facilitates spontaneity. By learning the muscle memory of a set of patterns in an art form, one can then improvise. I have explored how through Rhythm, pattern, and repetition, a space emerges for improvisation within a set form. In moments, rhythm evoked by

repetition can also facilitate a flow state.

Repetition and the Flow State

‘Repetition is not repetition’ because it can evoke a Flow state of connection and sometimes even states of transcendence. For example, in examples such as weaving, laying down stones, and land art. Perhaps in the Bone Woman story, an unusual flow state occurs as the lady walks under-water and is bitten by fish. She is in the flow of walking that she doesn’t even notice the differences the fish make emerging. While this eating away at her seems a somewhat violent loss, on the other hand, she is shedding a skin that deeply connects her to the natural world, losing her human skin to become wild. In this way, the repetitive action connects her to a new realm of life. Another emergent property of repetition which flow states can evoke is transcendence and states of revelry. For example, in many rituals, we can see this. The ceremony of chanting together, carnival repetitive motions, evokes a state of transcendence that moves beyond everyday feeling. The collective dance of man and women in the Bone Woman story is truly transformative … it reanimates the old man and creates youth. ‘Movement is bound to music... the Greek root of the word related to all arts of the muses’ (Warren, 2023, P.15). This is the opposite of activities and material connections that have been ‘standardised and serialised’, following ‘replicability and reproducibility – a form of repetition that is more industrial (Groys, 2022, P.53). Groy’s then compares this to the material consumption and the individual's inner life becoming industrialised and repeatable. This contrasts material repetitions that facilitate particular and individualised connections to the natural and material world, often invoking a flow state. Weaving was seen as the poet's role in the Greek times. This synergy seems to suggest poets weave together experience. Weaving itself is a repetitive action that connect the subject and object in a flow state. Thus, it is clear to see that some forms of repetition evoke the emergent property of flow state and transcendence or even transformation. Another emergent property of repetition is unity.

Repetition and patterns of unity

‘Repetition is not repetition’ because it allows for the emergent property of unity, particularly within patterns. If it wasn’t for imperfect repetition, we wouldn’t be able to connect with the particularity of something. When something is repeated, a sense of togetherness can form between persons – human or other. For example, storytelling can be compared to making love: a repetitive yet imperfect repetition - storytelling and conversing ‘is sex for the soul’ (Allende, 1999), P.63). In a reciprocal relationship with the world, every connection is different. For example, the repetitive act of making love can open a space for spontaneity and deep connection where ‘the goal is nothing, the movement is everything’ which is anti-capitalist repetition (Bauman, 2000, P.11). An example of repetition creating unity is the continual blowing on the ass of Muskrat, which unifies the process of creation as a continual manifestation and emanation. In a way, becoming with the world presents repetitive patterns as constantly evolving, as the subject and object merge. The natural world, all living things, and Humans are in a sense imperfect repetition, which is reflected in the storytelling tradition. Repetition provides the container for life and story to occur - the seasons, for example, the cycles of planets, the cycles of the period for a woman. These cycles are repetitions but are not perfect repetitions. Each one is opening a space for difference. I have explained how unity can be created through repetitive patterns, particularly in how nature repeats itself imperfectly, to demonstrate how repetition is not repetition.

Conclusion

Journeying through different creative repetitions has opened many spaces where ‘repetition isn’t repetition’. It leaves me with the inquiry into how monotonous repetitions differ from repetition that invites creativity and emotional expression. Many Oral cultures, within dance, song and story, honours this imperfect repetition at its very nature. Whereas, contemporary technocratic culture seems to honour and consistently attempts at perfect repetition, which isn’t natural and in-fact an impossible endeavour due to planetary limits and the natural order of imperfect repetition. Having looked at patterns in the arts, from ancient oral storytelling and ritualistic activity to contemporary forms of art where this applies, it seems Repetition is more than mere repetition: it is always in a state of becoming with, having an additional form or outcome. Some contexts of repetition facilitate this creative emergent property, while others stifle it. This is very curious and seems to distinguish between nature and artifice. Perhaps more artistic ways of being in the world - the reciprocal, transcendent connection, and communion with the world are formed in rhythms of repetition that open a space for spontaneity and transcendence. While industrious ways of repetition attempt at mere repetition without its vital counterparts. Pina Bausch’s dance - imperfectly repeated motions, evoke emotion and human connection like oral storytelling - the opposite of alienating repetition, which is monotonous. This invites further speculation.

Stories referenced

- The Bone Woman

- Wolverine makes the world

Images

- P4: Mask making, Pina Bausch

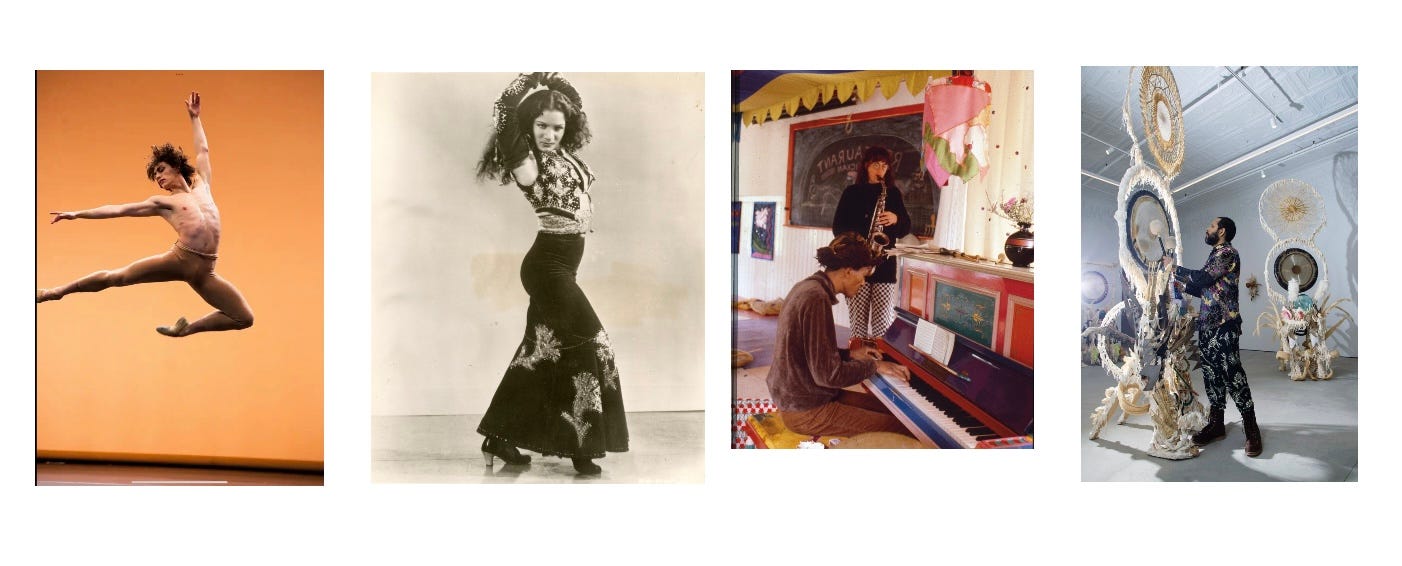

- P5: Ballerina, Flamenco, Moki and Don Cherry, Music Art Ritual

- P6: Land Art, Bread Artist, Barbara Hepworth, Serpentine pavilion.

Bibliography

Alain De Botton and Armstrong, J. (2016). Art as therapy. London: Phaidon Press Limited.

Allende, I. (1999). Aphrodite. Harper Collins.

Arendell, T.D. (2019). Pina Bausch’s Aggressive Tenderness. Routledge.

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bergson, H., Narcy, M., Renaud Barbaras, Bertrand Saint-Sernin and Worms, F. (1997). Henri Bergson. Paris: Les Éditions De Minuit.

Berger, J. (1972). Ways of Seeing. Edmonton, Alta.: The Schools.

Brandstetter, G., Polzer, E. and Franko, M. (2015). Poetics of dance : body, image and space in the historical avant-gardes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brenan, G. (1980). South from Granada : by Gerald Brenan ... Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brooks, D., Rowe, N. and Branch, S. (2005). The Poetics of space. Blackheath, Nsw: Brandl & Schlesinger [For] The English Association, Sydney.

Esquirel, L. (1989). Like water for chocolate. London: Black Swam.

Forster, E.M. (1989). Howards End. National Geographic Books.

Fromm, E. (1957). The art of loving. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Jemma Deer (2022). RADICAL ANIMISM : reading for the end of the world. S.L.: Bloomsbury.

Keith Thor Carlson, Kristina Rose Fagan and Khanenko-Friesen, N. (2011). Orality and literacy : reflections across disciplines. Toronto: University Of Toronto Press.

Macleod, I. (2023). Rituals for Life. Laurence King Publishing.

Mary Antonia Wood (2022). The archetypal artist : reimagining creativity and the call to create. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, Ny: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Marcuse, H. (1964). One-dimensional man : studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society. London: Routledge.

Pantelia, M.C. (1993). Spinning and Weaving: Ideas of Domestic Order in Homer. The American Journal of Philology, 114(4), p.493. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/295422.

Peters, G. (2012). The philosophy of improvisation. Chicago ; London: The University Of Chicago Press.

Plato and Francis Macdonald Cornford (2010). Plato’s cosmology : the Timaeus of Plato. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Rosa, H. and Wagner, J.C. (2019). Resonance : a sociology of the relationship to the world. Cambridge, England ; Medford, Massachusetts: Polity.

Scott, J.-A. and Springerlink (Online Service (2018). Embodied Performance as Applied Research, Art and Pedagogy. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Seamon, D. and Zajonc, A. (1998). Goethe’s Way of Science. State University of New York Press.

Schwarcz, V. (1991). No Solace from Lethe: History, Memory, and Cultural Identity in Twentieth-Century China. Daedalus,

Warren, E. (2023). Dance Your Way Home. Faber & Faber.

www.youtube.com. (n.d.). Brian Eno and James Bridle on Ways of Being | 5x15. [online] Available at:

[Accessed 27 Oct. 2023].